Observations

Of the four National Park lodges that have earned NPLAS Criterion Classification, the Ahwahnee is the newest in terms of original construction. Its six story central block would tower over most lodges, yet in the setting of Yosemite Valley it is stately rather than overstated. It is also the most "versatile" of the big four, offering a range of room styles, suites and cottages, and a variety of recreational activities. But not all at the Ahwahnee is what it seems...

above, the solarium shortly after opening. The stonework remains unchanged.

The Unlikely Spawn of Camp Curry

The Ahwahnee owes its existence to Stephen Mather. Like much of the modern National Park Service, it came about because Mather had a clear vision of how he thought things should be, and he used a combination of willpower, persuasion, and his personal fortune to make it happen. Until Mather's involvement, lodging in Yosemite Valley was a hodge-podge of campgrounds, shoddy 19th Century hotels, and the quirky sprawl of Camp Curry. Mather wanted to clean up the mess, and forced a merger between the two biggest concessionaires, The Yosemite Park Co. and The Curry Co.

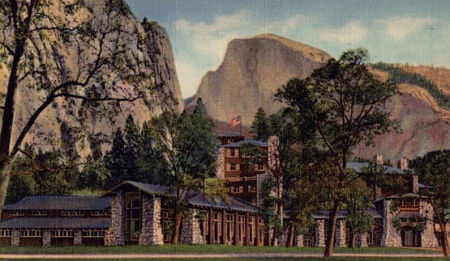

View of the dining hall wing, framed by the unmistakable visage of Half Dome.

With the dawn of the 1920s a lot of things were happening "behind the scenes" in Camp Curry. Founder David Curry had been lobbying for expansion prior to his death in 1917, and made numerous enemies at the Department of the Interior during the process. With son Foster Curry continuing his father's sometimes bombastic approach to managing the family fiefdom, the cries for expansion continued. Meanwhile the Curry's attractive and reserved daughter Mary had just graduated from Yale, and married a charismatic med student named Donald B. Tresidder in 1920.

Camp Curry was not the type of development Mather had in mind, but it was wildly successful and a popular, affordable destination for the average American. He ultimately brokered a deal with the Curry family, allowing not the substantial expansion but rather a grand hotel concession, which was to be The Ahwahnee. Foster Curry would continue as camp master, but the management of the overall company would fall to Mary, who presented a more appropriate image to Washington. As Mary was far too shy to tackle that role, her husband would be the first president of the company. Donald Tresidder eventually became president of Stanford University as well, and performed both tasks until his death in 1948. Mary did take on the role as president of The Yosemite Park and Curry Company at that time, and remained so for the rest of her life. The Tresidders lived in the penthouse apartment at The Ahwahnee, which is where Mary died in 1970. The apartment was then converted to a series of rooms (Mather, Spencer, Underwood, and The Mary Curry Tresidder) that can be combined a variety of ways to create suites or one large suite. It was in just such an arrangement that Queen Elizabeth was a guest in 1980.

Original Construction

Viewed from the meadow, The Ahwahnee almost appears to have risen from the ground. It fits the setting so naturally, as if it collected raw materials from the valley floor as it surfaced. The weathered granite and But again, not all at the hotel is what it seems.

Because the resources within a national park are protected by law, the materials to build The Ahwahnee had to come from outside Yosemite. This may not sound unusual today, but consider that in 1926, roads for motor vehicles were still a relatively new phenomenon. For that matter, so were the vehicles. Hauling the materials for the Ahwahnee was the biggest test for the infant trucking industry thus far, and it was done over the grueling Yosemite access roads. The roads were nothing short of ghastly; the truckers of the 1920s would consider today's narrow twisting ribbons of pavement as luxury highways by comparison.

Cost overruns were rampant, mostly due to transport issues. Load after load of steel, stone, concrete materials, and interior timbers all made the treacherous journey. The "redwood" exterior siding was poured on site. That's not a typo. The exterior, which appears to be pine timbers with redwood panels, is actually tinted concrete that was poured into molds replicated from wood. The effect is so realistic that you just might need to touch the sides in order to be convinced. Many visitors are simply unaware, and assume they are staying in a wooden structure.

The illusions really begin upon arrival. The entry gates and roadway are impressive, and create the sensation that you are leaving the rest of Yosemite Valley and its crowded trappings behind. That's only partially true, because the Ahwahnee is a regular stop on the valley bus line, and you needn't be a registered guest to avail yourself of the public areas.

A rare quiet moment on the patio. Photo courtesy the National Park Service.

The main entrance to the building is through a porte-cochere on the north side. As entranceways go, it is hardly what you would consider stunning. In fact, the first impression is often disappointment, as it looks nothing like the photos most arriving guests have seen. Again, all is not what it seems...just prior to opening in 1927, employees noticed that the grand entryway on the east side of the structure smelled terribly of truck fumes. This was due to the proximity of the service and delivery area of the hotel. Not only was the entry area smelly, it was noisy, and vehicular access looked as if it might conflict with the delivery trucks. With the gala opening looming in just ten days, it was determined that a temporary change to the guest entry route would be significantly less of a logistical nightmare than revamping the service and supply area.

A port-cochere and temporary walkway to the lobby were hastily built, just in time for the opening. This route was used until World War II, then re-routed slightly for the 1946 re-opening. This "temporary" north entry is still in use today; what was originally designed as the entry has been closed off from the exterior and now serves as the lobby and patio bar.

The most striking thing about the lobby is arguably the tile underfoot. It appears to be a carefully crafted native American creation, but it is actually a carefully molded industrial American creation...the tiles are rubber. Up to this point, from the porte-cochere, through the walkway and up to the front desk, the first time guest continues to be underwhelmed.

Move beyond the lobby area, to either the Great Lounge or the dining room, and the grandeur of the Ahwahnee unfolds immediately. The Great Lounge with its 24 foot ceilings is bookended by enormous fireplaces. The decor -- all with an odd blend of American Indian, craftsman, and art deco -- creates an impression of outdoorsy luxury. It's exactly what Mather wanted, brought to reality by the efforts of master interior designers Dr. Phyllis Ackerman and Dr. Arthur Upham Pope.

The Great Lounge has a couple of "hidden" gems for guests to lose themselves in; the writing room, solarium, and mezzanine level all feed the imagination. Taken as a whole, the Lounge is overwhelming. Guests looking for a quiet evening with a book need to search out an obscure corner somewhere, or run the risk of being overwhelmed by the room. During sunlight hours, the effect of the stained glass top pieces can be hypnotic. The room reveals itself in many ways through the day, and it is worth taking time to admire these subtle changes.

Just a few moments in the Great Lounge are enough to convince even the most jaded guest that The Ahwahnee is a special place. Afterward they return to the elevator lobby and general lobby, and the details begin to reveal themselves...hand-hammered lanterns, Indian motif in places you hadn't noticed before. In every glance, every direction, an artistic feast awaits the eyes. Even the lobby restrooms are cause for admiration.

The dining room is another of the public areas that must be seen to fully appreciate its grandeur. The ceiling ridgeline soars 34 feet above the floor, and features massive trusses -- which we're told are sugar-pine from outside the park. But look closely at the tree trunks that stand nobly to support the trusses. These too are molded concrete, stained and painted to replicate real logs. The wrought iron craftsman style chanedliers are simply stunning.

The knock on dining at the Ahwahnee is that the food doesn't quite equal the room. How could it? In all honesty the food and service are excellent -- it's important to remember that the overall experience is what counts. Turn that credit card loose, and you'll have the meal of a lifetime.