The Original Inn

Herbert Lore built the first Painted Desert Inn, called The Stone Tree House, in 1924. The exterior was striking, featuring locally collected petrified wood held together with a mud mortar. This was a two-story structure that could be considered similar in style to "National Park Rustic," far different from the Pueblo Revival structure we see today. Records indicate that the original building had no electricity -- the site was quite remote in the 1920s -- and water had to be delivered by rail and trucked in.

above, the original Stone Tree House. This view is from the rim looking back toward the road. The reception entry here on the lower level corresponds to the downstairs tap room entry today. In other words, what we think of as the "front" of the Painted Desert Inn was at the "back" of this image. The enclosed porch above the entryway afforded an excellent view of the desert. When the building was redone as The Painted Desert Inn in 1937, this porch was left as an open portico.

High Style on the Desert Rim

When the National Park Service purchased the Painted Desert Inn in 1936, it was planned to rehabilite the existing Inn and provide running water and electricity. Engineers found that the clay soil below the building was steadily eating away the mortar, and that entirely new construction made a lot more sense.

Unfortunately it was politically incorrect to fund new construction during the Depression, so the Park Service proceeded under the guise of "rebuilding." The limited funds were used to cover the cost of obtaining materials from National Forests, which had to be called "thinning" or forest maintenance in order to be approved. The NPS then used labor from the Civilian Conservation Corps, which were camped at the Rainbow Forest south of the railroad. Thus the Painted Desert Inn is one of the few examples of National Park architecture built during the 1930s.

According to NPS records, site supervisor Lorimer Skidmore did manage to use a few of the original walls, although they are unrecognizable. All walls were deemed unsafe, so even those that were saved were significantly reinforced and given new footings, and eventually covered with lime plaster and putty. Ceilings were constructed of pine beams with aspen savinos for a traditional pueblo look. Floors were built of concrete, flagstone, and in prime retail areas, wood.

The exterior corners and openings were finished with sweeping radii to soften the look of the building. The overall image is that of a multi-tiered structure that seems to be one with the terrain, which probably reflects Frank Lloyd Wright's influence on Lyle Bennett. The Painted Desert Inn was and is an imaginative and compelling structure.

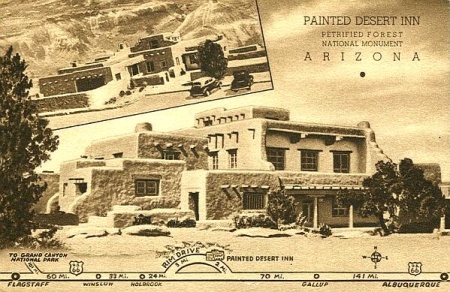

above, a vintage postcard with two different views of the Inn. The larger, lower image shows the view looking back from the rim; the lower entry doors go into the tap room. During the Stone Tree House era of the 1920s, this was the main entryway into the reception area. During the Harvey era of the 1950s, this entry was probably only used by employees. Compare this with the image of the original Stone Tree House above; the open porch over the lower entry here is approximately in the same location as the original enclosed porch over the same lower entry.

Although the name Mary Jane Colter is strongly tied to the Painted Desert Inn, her role was primarily that of an interior update for the Harvey Company. The architectural artistry of the original structure must be credited to Bennett, who used a combination of skylights, porticos, and Indian themes to create a southwestern masterpiece. Like a Great Kiva, the interior virtually glows with a light that is both earthy and otherworldly.

The main focus of the Painted Desert Inn was its function as a dining facility and gift shop. Lodging rooms were a reflection of time. Where the original Stone Tree House had inn-style guest rooms, the new rooms had exteriors that seem to borrow from "motor hotel" courtyards that were springing up around the country in the late 1930s. These were simple facades with individual exterior doors, separate from the main entries. The six rooms were small -- primitive by today's standards -- although each had a fireplace and individual bath. By 1940s standards, they were stylish and downright luxurious.

Sometime after the concession was purchased by The Fred Harvey Company, the lodging function was discontinued. Based on just six rooms, it is doubtful that it was ever operated profitably considering the level of service that was provided. Visitors today who venture around the structure can peer into these rooms, which are in a state of utter disuse. Rehabilitation of at least one room to its 1940 condition is a top priority for NPLAS Restoration Advocacy Program -- imagine the thrill of spending a few unhurried moments in of the Painted Desert guest rooms.

Reasons for the Harvey purchase are unclear. The Petrified Forest National Monument was an exotic location in the American psyche; it was known to be along a lonely stretch of Route 66. Because of a Humphrey Bogart movie called The Petrified Forest, the idea of an isolated cafe in the stirred both romance and fear for the average American. Whether the Union Pacific thought it would capitalize on this, or viewed the road as a threat to its rails, or was pressured to take this concession by the NPS; the details have been lost to time.

In any case, The Harvey Company put substantial resources into renovating the decade-old structure. Star designer Mary Jane Colter was brought in to bring the building up to snuff. She retained Hopi artist Fred Kabotie to design a series of murals and other artwork, some of which is well preserved today. If anything, Colter's and Kabotie's efforts enhanced the Painted Desert Inn, rather than modifying Bennett's original vision.

Even with the addition of Harvey Girls, the Painted Desert Inn didn't generate an exciting amount of revenue. By the late 1950s the Harvey Company was promoting it solely for dining and souvenirs, and by 1963 gave up on it. Benign neglect took its toll on the building, and despite some work in the 1970s, by the late 1980s it was noticeably disintegrating. Fortunately preservation efforts began in earnest, and the results are to the credit of the National Park Service.

above, a colorized image from the 1940s. This is probably from an authorized "Fred Harvey Company" postcard and was probably sold right up to 1963. It was typical of the Harvey Co. to use colorized images for decades, regardless of how dated the subject matter was. Although essentially accurate in this postcard, the artist did enhance and brighten the exterior colors. The color treatment, doors, and windows seen today are an excellent restoration of how the Painted Desert Inn appeared in its heyday.