Observations

For most of its existence, Paradise Inn was the Rodney Dangerfield of park lodges: No respect. Grumblings about demolition were voiced as early as the 1930s, and by the 1950s the consortium that built it said "enough" and gave the maintenance-intensive structure to the American people. Park Service studies repeatedly trotted out recommendations to torch the Inn to make way for a modern, full-service resort hotel. Destruction was a virtual fait accompli during the Mission 66 years, but somehow the old building survived.

A vocal minority of impassioned Paradise Inn fans refused to let the building go without a fight. Thought of at first as wacky preservationists, it was simply a matter of time before the American public woke up and realized the importance of the old lodges. By the 1980s and certainly the 1990s, the "no respect" was a fading memory as Paradise Inn was once again a destination unto itself. It must also be noted that the Park Service, once firmly in the demolition camp, is now the leading protector of historic structures such as Paradise Inn. [Unfortunately the nearby visitor center from the Mission 66 era was not deemed worthy of preservation. Ironic, considering the Inn was eyed for demolition by the same folks who cut the ribbon on the infamous "spaceship" -- Editor]. Although there are many guests today who simply don't "get it" that the Paradise Inn is a sort of living museum, and instead are quite perturbed that it lacks the plush conveniences of a modern Holiday Inn.

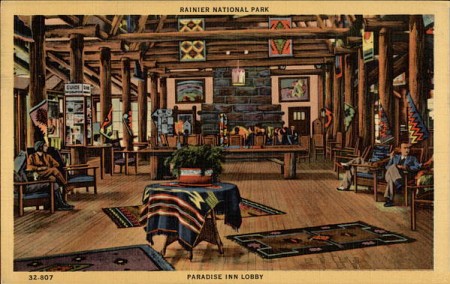

These vintage postcard images were used first as a black-and-white, then in the colorized format seen here. The image above was sold and mailed by thousands of visitors well into the 1950s, even though the image dates from circa 1917. The giveaway is the absence of the mezzanine, which was installed in 1925. Look closely at the beams at the mezz level in this image, then compare to the large photo at the top of this webpage. Below, another view of the same general area, this one from mid 20th century.

Paradise Inn is closely tied to man's history and experience in the park, probably more so than any other National Park lodge. Early guests would often spend a week at the Inn, enjoying horseback riding, golfing, and other leisure activities offered. These faded as more adventurous recreation gained popularity. Paradise Inn hosted Olympic trials, and at one time was the foremost winter sports destination in the Pacific northwest. It offered one of the first ski lifts in the region, a rope tow that operated into the 1970s. In the late 1960s, famed mountaineer Lou Whittaker was the Guide Service contractor, and his alpha male presence added a certain outdoorsy elan to the Paradise complex. The Inn and Climber's Guide Service long had a symbiotic relationship (the Guide Service building was constructed and furnished by Rainier National Park Co.) and to this day the Inn is the site of many congratulatory post-climb meals. It was, and continues to be, second only to the mountain as the average visitors' most identifiable memory of Mt. Rainier National Park.

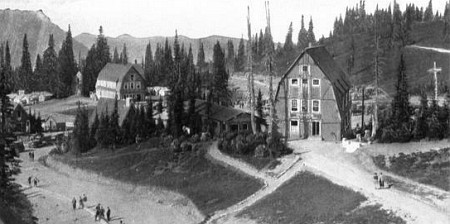

Above, this vintage view shows the Paradise-Inn styled Guide Service building in the foreground. Part of an old canvas cabin complex is visible in the left-hand side of the photo. That area is now a parking lot.

Most of all, the location has a palbable remoteness unlike other lodges. By comparison, The Ahwahnee has the hum of Yosemite Valley activity right outside the grounds, El Tovar has the constant canyon rim traffic, and even the Old Faithful Inn is part of a sprawling village complex. Not the case at Paradise, where despite the proximity of the guide service, visitor center, and other facilities, nighttime feels as if you might as well be on the moon.

Above, one of the cozy nooks built into the mezzanine. Photo courtesy the National Park Service. Below, early 1950s guests warm by the fire at the south end of the lobby, where Hans Fraehnke's massive clock dominates the decor. Although the attire and some of the furnishings have changed, this scene is repeated almost daily.

Rainier's famous fog often conspires with the evening air to create a chilling dampness. Even at the height of the summer solstice, nighttime occasionally brings snow flurries to Paradise. Thus -- unlike the other great lodges mentioned above -- guests rarely head outside for an evening stroll. While the patios at many lodges are frequently filled to capacity, Paradise guests head indoors. The lobby, although vast, takes on the warm intimacy. Decorated with massive fireplaces, hand-carved tables and decor, it conjurs visions of a great Nordic lodge hunkered down for the winter.

This great room isn't cozy by design, but when guests sink into one of the massive couches in front of the fire, it's hard to convince them otherwise. On the other hand, it is far from being the most impressive of the great lodge lobbies. Yet somehow Paradise Inn manages to convey the feeling that it is both intimate and grand at the same time. And if you happen to be behind the doors when the weather is nasty, it has the added dimension of feeling like a safe haven. Add it all up, and it's understandable that although Paradise Inn is seldom rated as the best National Park lodge, many rank it as their personal favorite.

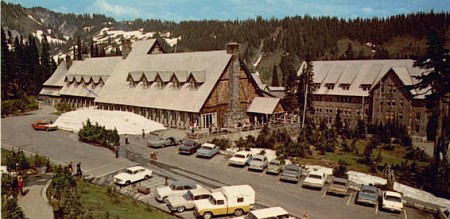

Above, this mid-1960s photo gives a good view of the relationship of the 1920 Annex to the original lodge. The transition from one building to another is obvious as you cross a "bridge," but it is close and seamless -- and some find the layout confusing -- that many guests don't realize that their room is actually in the Annex.

No discussion of Paradise Inn is complete without mention of Hans Fraehnke, the fabled German craftsman who hand-built many of the odd wood creations located throughout the great room. The passing of time has understandably romanticized Fraehnke, he is oft-described as "mysterious" and "little is known," etc. Today this humble carpenter has become a legend of mythical proportions. Some authors have mistakenly perpetuated the story that he worked alone through the winters while the Inn was being constructed; others claim that he reported to work faithfully on the 1st of March each year, regardless of weather conditions.

Like most legends, the Fraehnke stories are based on shards of information that greatly distort the truth. Fact is that Fraehnke was a fairly well known craftsman in the region, who had a carpentry and custom furniture shop in Fife. Originally from Luebeck, Germany, he was an extremely private man. Keep in mind that he began working at the Inn during the height of World War I -- a time when many things "German" were being re-named to remove any stigma -- and it stands to reason that he kept a low profile due to the political climate.

The most reliable sources (including the NPS) generally agree that Fraehnke was involved from 1916 through 1923. Fraehnke was interviewed for a 1949 feature article in a Tacoma newspaper, but he remained a man of few words. That article was the source of the annual March 1st trek, but the claim did not come from Fraehnke.

What we can safely record as historically accurate is this: Next time you visit Paradise Inn, take a moment to reflect on the artistry and craftsmanship in the tables, the clock, the piano, the mail drop, and other Fraehnke creations. Recognize that they were constructed by an honorable man who was devoted to his work, who would require no recognition other than your quiet appreciation for his efforts. That seems to be the way he would want it.